A History of the Blueprint

Blueprints were invented a generation before the Civil War by John Herschel, a chemist, astronomer, and photographer, in 1842. Herschel developed the cyanotype process that started with a drawing on semi-transparent paper, weighted down on top of a sheet of paper. The paper was coated with a photosensitive chemical mixture of potassium ferricyanogen and ferric ammonium citrate (a hazardous chemical formula). Once the drawing was exposed to light, the exposed parts turned blue, while the drawing lines blocked the coated paper from exposure and remained white.

The blueprint process eliminated the cumbersome expense of hand-tracing original drawings. By the 1890s in architectural offices, a blueprint was one-tenth the cost of a hand-traced reproduction and could be copied in a fraction of the time using the photochemical process.

One hundred years later, in the 1940s, blueprints were replaced by diazo prints, aka whiteprints or bluelines. Diazo prints had blue lines on a white background. They were easier to read and faster to make. The process was simple, the machines were not overly expensive for reprographic companies and didn’t need extensive maintenance. For decades, bluelines were the way to make copies of architectural drawings. To this day, they are often called blueprints.

By the 1990s digital drawings created with computer-aided design (CAD) went mainstream. Digital drawings were completed on powerful desktop computers, put on a portable disk drive and delivered to a plotter at a reprographics shop for black and white copies. Plotters are expensive and require specialized maintenance. They were soon replaced by large digital printers.

You would think that paper drawings are nearing obsolescence. Not so fast.

Before construction begins on a jobsite, drawings will be printed and reprinted numerous times over by architects, project managers, building owners, and contractors. Every change order requires sets of new prints. Your friendly, neighborhood reprographics shop gets an average of 30 print requests a day from the construction industry. These shops print 12,000 drawings a year. But business is reported to be dropping off.

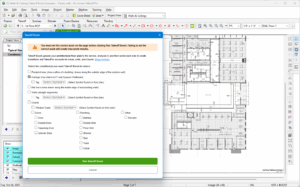

That’s because the same workflow of revised drawings is achieved using On-Screen Takeoff® software. Contractors can view plans, measure lengths and volumes, and markup plans on a computer screen. Plans are digital and color-coded and can be emailed as PDFs to the job site without printing a single sheet.

The printing costs often hit the subcontractors most. Even greater savings are in store by going digital, savings in time, gas, and unproductive travel time running revisions back and forth from the office to jobsites. Viewing and sharing plans digitally is here to stay. Today, project managers get revised plans by email, calculate new takeoff measurements and quantities with blazing speed using On-Screen Takeoff.